One reason the plague was able to spread so massively across Europe during the Middle Ages may have been that the bacteria that caused the disease lay hidden, in some unknown animal reservoir, for centuries, a new study reports.

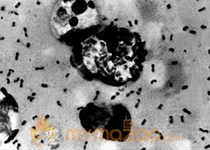

In the study, researchers in Germany hypothesize that the bacteria Yersinia pestis, which causes plague and killed millions of people, may have survived in Europe in an unknown host during the second plague pandemic, which lasted from the 14th to the 17th century.

The idea came after the researchers analyzed the DNA from the skeletal remains of 30 plague victims who were buried at two grave sites in Germany. The researchers compared the data from the genetic analysis of these plague victims to the results of previous genetic analyses of skeletal remains of European plague victims from other countries.

They found that five of the German plague victims were infected with genetically identical Y. pestis bacteria, even though they lived about310 miles (500 kilometers) and 300 years apart. The German plague victims also had Y. pestis that were genetically similar to that of far-away plague victims, in Britain and France, according to the research, published today (Jan. 13) in the journalPLOS ONE.

It has become evident in recent research on plague DNA collected from people infected during each of the three major pandemics that all of the pandemics originated from Central Asia (China), said study author Holger Scholz, a molecular biologist and infectious disease researcher at Bundeswehr Institute of Microbiology in Munich, Germany. But the question on the researchers' minds was why the second pandemic lasted such a long time — three centuries — and wiped out about one-third of the continent's population, he said.

ew research on old disease

The previous explanation of how the plaque reached Eastern Europe is that the bacteria were introduced via the major trade route from Asia, known as the Silk Road, Scholz said. From there, the bacteria was thought to be transported by sea and introduced to other parts of Europe in several waves, he said.

Rats on the ships and their infected fleas, which can transmit the plague bacteria when they bite people, could have played an important role in disseminating the disease, Scholz told Live Science.

But in the new study, the researchers excavated human remains from victims of the second plague pandemic, including the period between 1346 and 1353 known as the "Black Death." This is when bubonic plague was at its peak in Europe.

"Our findings show that at least one genotype of Y. pestis bacteria may have persisted in Europe over a long time period in a not-yetidentified host, possibly rodents or lice," Scholz told Live Science. This is new thinking, suggesting there might have been "good conditions" in Europe for the plague agent to survive there, he explained.

It is likely the second plague pandemic resulted from a combination of the infectious agent being continually reintroduced in waves to Europe, as well as the agent surviving for long periods in an unknown host, Scholz said.

New explanations

People who have bubonic plague develop symptoms such as fever, headache, chills and weakness as well as swollen and painful lymph nodes in the areas closest to where the bacteria first enters their body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

These days, plague cases still occur, but can be treated with antibiotics.

Scientists can now use modern methods to investigate ancient medical problems, and the first detection of Y. pestis in the remains of plague victims from the Middle Ages occurred in 1998. Since that time, researchers have been working to pinpoint the causative agents of plague for each of the three major pandemic periods.

But not everybody is convinced that the new explanation proposed in this study is supported by the available evidence.

The question the researchers are trying to address in this new study — did the plague hang around in a reservoir in Europe, or was it continually reintroduced from Asia during the second pandemic — is an interesting one, said James Bliska, a professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Stony Brook University in New York, who was not involved in this research, but has conducted studies on Y. pestis and plague. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

However, "the results in this paper are limited and preliminary," Bliska said.

The data from this analysis doesn't strongly suggest that genetically related bacteria were necessarily persisting in a host in Europe, and it still could be that independent reintroductions of the same bacteria were occurring, Bliska told Live Science.

The study's sample size is small and there are alternative explanations to their finding of identical strain genotypes of the bacterium in these plague victims, he said. The findings could be due to chance and a larger number of samples may have showed more genetic diversity in the bacteria, he also noted.

For the people in Europe during the Middle Ages, it made little difference whether they were dying from plague continuouslyintroduced to the continentor from plague that was introduced only once or twice, Scholz said. But this might be a modern-day worry for scientists should additional research find that given the right conditions, it's possible for plague to persist for a long time, he added.